Andrea Gilbert thought she knew what would happen to her brain.

The 79-year-old retired attorney, who has Alzheimer’s disease and receives care at Harborview Medical Center in Seattle, agreed to donate it for research in 2023. She hoped to help scientists unlock the keys to a disease that had left her writing notes to remind herself if she’d already brushed her teeth.

The fate of that program is now in limbo because the Trump administration has upended the system that funds biomedical research.

“It’s going to go one way or another. I’m not taking it with me,” Gilbert said from a hospital bed as she received an infusion of a drug designed to prevent the disease from worsening. “I hope it gets used well. But, you know, you can’t guarantee anything.”

Thousands of grants, including many at public universities and on topics as politically benign as Alzheimer’s, have been caught in what critics say is an unprecedented slowdown of the American research system that is threatening to upend universities and halt progress toward medical innovations, treatments and cures.

Even the temporary slowdown threatens to hamper or scuttle programs that have been decades in the making — and some of which are also actively treating patients.

The National Institutes of Health has been the primary funder of the University of Washington’s Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC) since 1985. The program supports a brain bank that accepts more than 200 donations yearly and is preserving more than 4,000 brains. The center’s grant funding, which is waiting for renewal, expires at the end of April. But grant decisions across the nation have slowed to a crawl, according to court filings.

The program has focused on unraveling the basic biology of the disease and factors that counter it. It discovered or helped identify three genes in which mutations cause Alzheimer’s.

The situation has left Gilbert’s neurologist, Dr. Thomas Grabowski, confused and scrambling. What will happen to patient care and the brains banked for research at Harborview?

“We’ve gone through a bunch of contingency planning,” said Grabowski, who is also the director of the ADRC. “When it starts to look like multiple, multiple, multiple months, then there’s not a good answer to your question.”

Dr. Dirk Keene, a professor and the director of neuropathology at UW Medicine who leads the brain bank, said if federal funding dries up, he’ll go to almost any end to “honor the gift” of people’s donation.

“I’ll beg, I’ll borrow. I don’t think I’ll steal, but I’ll do whatever I can to find money,” Keene said.

Legal battle

Universities are reeling. The Trump administration has executed a flurry of research grant terminations at large, private institutions like Johns Hopkins and Princeton University. In a recent court case against NIH, the American Civil Liberties Union argued that the administration targeted cuts to grants about topics it disfavors like diversity, LGBTQ issues and gender identity.

Among public universities, the University of Washington is one of the hardest hit, and researchers and students have said the fallout from the cuts has upended their careers and forced some to consider leaving the U.S.

“We’re going to have a big brain drain in the U.S. of these really talented folks,” said Shelly Sakiyama-Elbert, the vice dean of research and graduate education at UW Medicine. “It’s not just a switch that you flip, right? If people move out into another direction with their careers, they often don’t come back.”

In a statement to NBC News, NIH said it was dedicated to restoring “gold-standard, evidence-based science.”

“NIH is taking action to terminate research funding that is not aligned with NIH and HHS priorities,” the federal agency said. “As we begin to Make America Healthy Again, it’s important to prioritize research that directly affects the health of Americans. We will leave no stone unturned in identifying the root causes of the chronic disease epidemic as part of our mission to Make America Healthy Again.”

A legal battle is ongoing over the cuts and funding pauses, but any permanent resolution is likely months away. The state of Washington is one of 16 that filed a lawsuit against NIH and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, alleging that the Trump administration has terminated hundreds of grants through “shoddy justifications” and delayed decisions on billions of dollars in research funding. The attorneys general have asked for a preliminary injunction to quickly restore the flow of funding. A judge is slated to hear arguments in early May.

Thousands of grants, millions of dollars

The University of Washington is one of the top public universities for biomedical research and a place where basic science discoveries are translated into clinical trials and hospital care.

In a court filing, the university said it receives more federal research dollars than any other public university. Many of those dollars go toward UW Medicine, the university’s hospital system and its clinical research hub.

The university said it had received about 1,220 grants from NIH and about $648 million in funding last fiscal year.

But this year, the grant approval process came to a sudden halt.

As of April 1, the university said more than 600 grant proposals were waiting for review or stuck at some juncture in that process. Another 12 grants or subgrants have been canceled outright, including one for studying the prevention of chlamydia infections and another about the recovery of sexual assault victims, court documents say.

The grant slowdown has forced the university to implement furloughs, plan for layoffs and reduce graduate admissions by 25%-50% for next year, according to the filing. The university has implemented a hiring freeze, and researchers across campus are feeling the effects.

David Baker, a professor of biochemistry at the University of Washington School of Medicine, won the Nobel Prize in 2024 for his research on protein design. But Baker, who is the director of the Institute for Protein Design, said about 15 of his graduate students and postdoctoral researchers within his group are now seeking positions outside the U.S.

“There’s so many amazing people who want to come in, and we can’t take them,” Baker said. “The Nobel Prize was just a little blip. But things have gotten quite bleak.”

Dr. Rachel Bender Ignacio, an infectious disease researcher and physician at UW Medicine and a partner institute called the Fred Hutch Cancer Center, cut her own salary down to 60%, choosing to distribute the rest among junior scientists and other staffers within her 15-person clinical research group.

“Right now, due to the funding cuts, we are unable to enroll any more participants into federally funded studies, or start new studies, or do really any new work,” said Bender Ignacio, who said she was concerned for patients enrolled in HIV clinical trials. “We often are conducting research with people who are in clinical care and they’re receiving state-of-the-art treatments as part of research.”

The pipeline

For Alzheimer’s disease, research breakthroughs are increasingly being evaluated in clinics, which means disruptions to funding could have an effect on patient care.

Gilbert, who is chatty and eager to laugh, was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease in late 2023, soon after lecanemab, a new therapy designed to slow the disease’s progress, became available.

In December 2023, Gilbert was one of the first patients at Harborview Medical Center to receive a dose of lecanemab, the first disease-modifying drug approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use against Alzheimer’s in people with mild cognitive impairment.

Gilbert visits the hospital, part of the UW Medicine system, twice a month for an infusion of the drug, which is designed to clear amyloid protein, one driver of Alzheimer’s disease, from her brain.

“They said, ‘This is not going to reverse the effects of Alzheimer’s, but hopefully it will slow it down,’” said Chris Gilbert, her son. “All things considered, she’s doing pretty well. She still lives home alone, independently.”

On a sunny April morning in Seattle, Andrea completed her 36th infusion, greeting nurses and fellow patients as if they were old friends.

Andrea and Chris Gilbert said they believed the drug, and her excellent care at Harborview, had prevented her symptoms from worsening. They noted that since her diagnosis, Andrea had increased her score by one point on a 30-question cognitive assessment used to evaluate Alzheimer’s patients.

Grabowski, the neurologist, said other, newer Alzheimer’s drugs are in the pipeline, in part because of NIH’s commitment to addressing the disease.

“They were all at some point funded by NIH in the development stages, preclinical work,” Grabowski said. “So, if you took away NIH funding altogether, you would find this whole pipeline to therapy kind of drying up.”

But over the past few months, Grabowski said he’s grown increasingly worried about his center’s funding.

Grabowski said the center had applied for a grant renewal of $15 million in direct costs over the next five years, but he was uncertain if, or when, the funding might be approved. He said the center receives roughly 85% of its funding from the federal government.

It’s not uncommon for NIH to renew a grant after it expires, but Grabowski said “unprecedented uncertainty” at NIH has left him largely in the dark about his center’s future.

When the Trump administration took office, it temporarily paused communications from health agencies, including scientific advisory council meetings in which grants are reviewed.

Grabowski said he’d received little communication from NIH about his 940-page application until late March, when staffers asked for a revised grant application to address DEI, or diversity, equity and inclusion.

He worries about the fate of the center and its long-term studies, including one that is following 450 people, including Gilbert, until death. Ideally, each participant will receive a yearly evaluation of their health and memory loss until their autopsy and brain donation.

On shaky ground

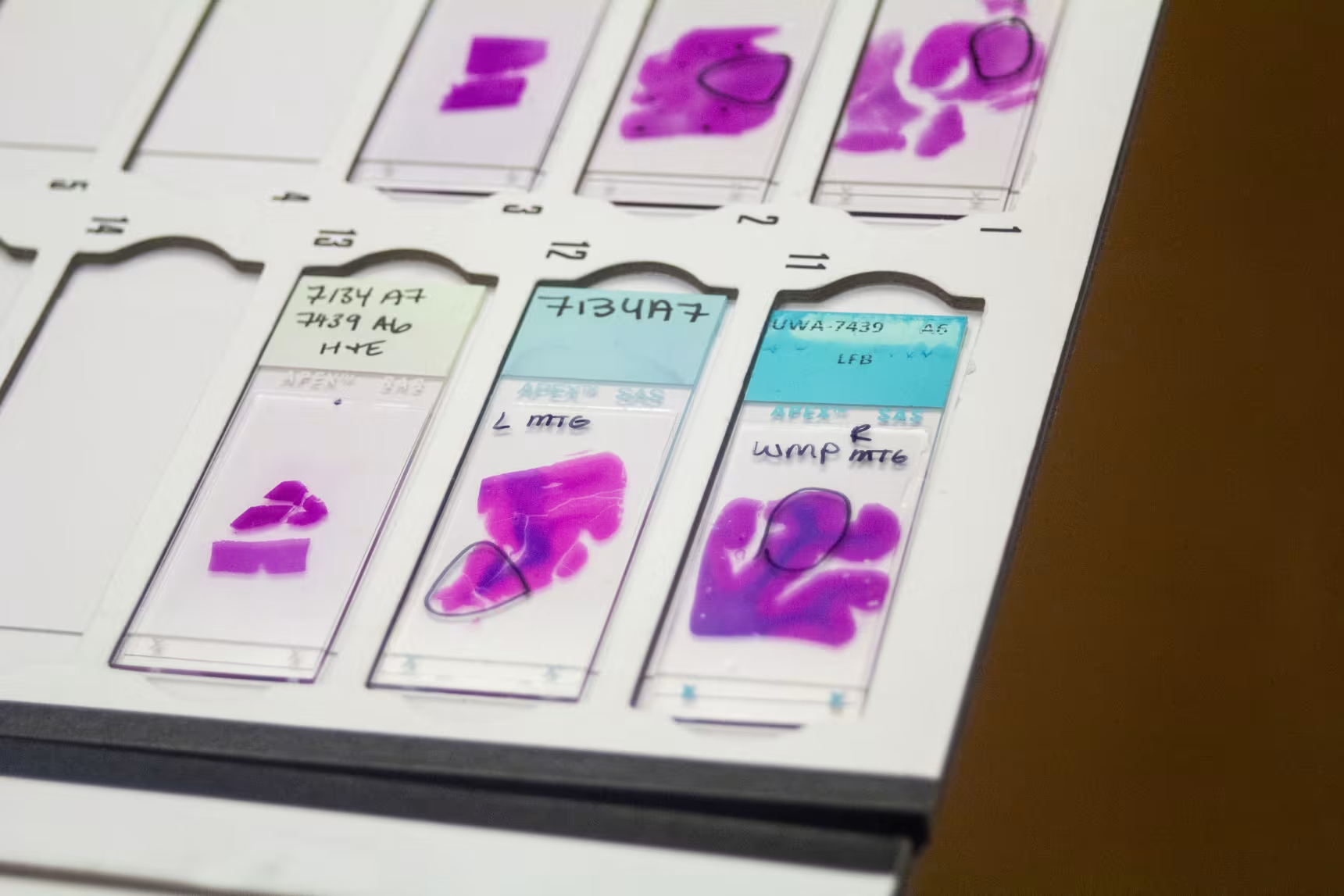

As researchers search for new treatments, the brain bank at Harborview Medical Center is an invaluable resource. Last year, it shared about 11,000 tissue samples with researchers.

It’s a busy operation. Teams are on call around the clock to retrieve brains within 24 hours after a donor’s death. Each year, between 200 and 240 people donate their brains for research at Harborview.

Once collected, a brain is dissected and a portion is frozen in a freezer that’s minus 80 degrees Fahrenheit. The remainder is sliced into thin samples and analyzed with a microscope for abnormalities.

“We have brains that were donated 40 years ago that we still use very frequently,” Keene said.

In addition to the concern about the ADRC, Keene said another federal NIH grant that supports research to find the brain cells most vulnerable to disease expired at the end March. That grant, which totals nearly $7 million in direct costs for several projects, also helps to fund the brain bank.

“If all of our funding collapses, the most important thing is being able to still honor the commitment that we’ve made to these people,” Keene said. “That’s our priority, is to get these brains in the lab and preserved, and they can sit for 10 years if that’s when the funding comes back.”

Chris Gilbert said he didn’t understand how research into Alzheimer’s could be on such shaky ground.

“Drugs like Leqembi give people promise and hope, and it’s the same thing with the brain tissue study,” Gilbert said, referring to a brand name of lecanemab. “All those things contribute to finding cures and ways to prevent this and treat it. The fact that they’re cutting these things or putting them in limbo is really upsetting, and you know, I feel like they’re doing surgery with a chainsaw at the federal level.”

The University of Washington hosts one of 35 Alzheimer’s research centers funded by the the National Institute on Aging. The centers operate as part of a cohesive network and share data.

Grabowski said 14 centers are seeking grant renewals this year.

“Many of us are in the same boat” as the University of Washington, said Dr. Helena Chui, the principal investigator at the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at the University of Southern California. “It’s a very strong network, and it would be easy to wreck, but it took years to build.”

This article originally appeared on NBCNews.com. Read more from NBC News: